Should I Buy or Rent? A mathematical guide to help you keep up with the Joneses

Divergence has been the theme of my life since graduating from university in 2009. In a matter of two years, I’ve had classmates secure engineering jobs in AB, ON, and NL. Others took up graduates studies. Some became engaged/married. And finally, some friends have became homeowners.

The spate of adult-like behaviour got me thinking of a timeless question: should I buy or rent?

The common argument I hear for buying a property is that you are wasting your money when you rent. In other words, your monthly rent payment goes to your landlord’s pocket. These people claim you are better off putting your money into a mortgage, allowing you to transform a living expense into an investment. The problem with this argument is that it doesn’t look at how your mortgage payment is split between principle and interest, or how it is shared between your pocket and your bank’s pocket.

Take a look at the following case:

- You can rent for $900 / month

- You can have a mortgage for $1500 / month, which averages $900 a month in interest over the first 5 years of the mortgage

Which option do you choose?

The easy answer is probably to buy a home. In either case you are losing $900, so you might as well buy your own property.

A better answer might be “it depends”:

- How much is the mortgage?

- Do you have a down payment?

- Will you need mortgage insurance?

- What is the amortization period? And the mortgage term?

- What is the interest rate? Fixed or variable? What will interest rates be in 5 years?

- What are the conditions in the housing market? Appreciation, stagnant or depreciation, speculative?

- Are there condo / strata fees?

- How much will basic utilities cost?

- How much does it cost to rent in the area?

- What investment return could you achieve if you weren’t getting a mortgage?

- Are you thinking about moving?

- Are you thinking about going back to school?

- Would you rather travel abroad while you are young?

- What is the risk of each variable listed above changing?

It’s easy to see that buying a house can be one of the most complicated purchases you can ever make in life. Home purchases are likely driven by emotions rather than logic, and it doesn’t help that the math is extremely convoluted.

I’ve put together some graphs showing when you are better off renting than buying. Most of the graphs assume the following:

- $250,000 mortgage

- 5% fixed rate, 5 year term

- 25 year amortization

- 10% investment target

- $900/month rental cost

Mortgage insurance was not considered, which is applicable to purchases with down payments less than 20%. Mortgage insurance can be a significant cost to homeowners, second to municipal taxes.

The graphs in this blog post show the difference in return on investment (ROI) between buying a home, and renting + investing:

- a positive ROI indicates a financial incentive to buy a house

- a negative ROI indicates a financial incentive to rent

Return on Investment (ROI)

- gain = capital gains (house appreciation) + down payment + principle paid

- cost = mortgage payment + down payment + taxes + condo fees + utilities

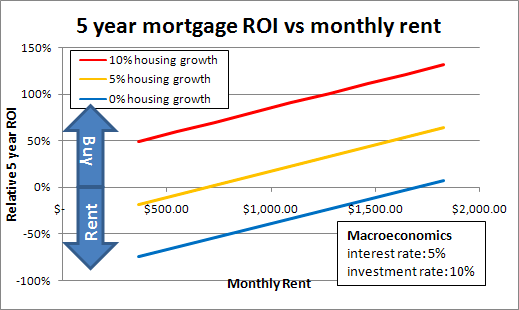

ROI sensitivity to monthly rent

Baseline scenario

Each line in the graph represents the growth rate of a housing market. In Canada, you can assume these examples:

- 0% growth for PEI real estate (stagnant / tepid growth)

- 5% growth for Toronto real estate (average growth)

- 10% growth for Calgary, Vancouver, St. John’s real estate (high growth)

As mentioned earlier, the calculations are based on:

- $250,000 purchase

- 10% down payment

- 5% fixed interest rate, 5 year term

- 25 year amortization

- 10% investment rate

A stagnant housing market offers almost no financial incentive to invest in real estate, however we’ll see below this may not always be the case.

The break point between buying and renting in Toronto is approximately $700 / month, based on the assumptions listed. You will be in a better financial position if you can rent an apartment for less than $700 and invest the balance of your money that would have gone to the mortgage, as opposed to getting a $250,000 mortgage at 5%.

A high growth housing market shows that it is never favourable to rent, but the problem with high growth housing markets is they are more volatile to other factors. Calgary and Vancouver both experienced a sour housing market relative to Toronto during the previous recession. These housing markets rarely sustain high growth for an extended period of time (see page 6).

Low investment rate scenario

The previous graph illustrates the ROI for various housing markets, assuming an alternative investment rate of 10%, but the reality is that most people who do not achieve those kind of returns. If we assume these people park their cash in a chequing or savings account, effectively a 0% investment, then buying a house always makes sense.

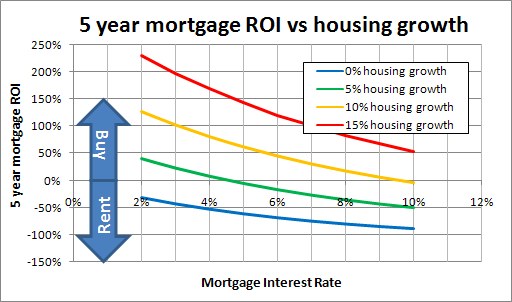

ROI sensitivity to housing growth

Baseline scenario

Baseline conditions:

- $250,000 purchase

- 10% down payment

- 25 year amortization

- 10% investment target

- $900/month rental cost

This graph shows the sensitivity of the mortgage ROI as function of housing growth and interest rates.

We can see with our baseline scenario that buying in a tepid housing market doesn’t make a lot of financial sense.

In an average housing market, like Toronto, there is an inflection point at 6%. You are better off renting at interest rates above 6%, while there is a financial incentive to buy at interest rates below 6%.

Our high growth housing market offers not financial incentive to rent, even at high interest.

$600 monthly rent scenario

This graph shows the sensitivity with $600 rent.

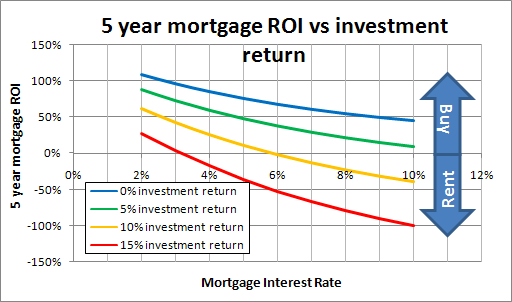

ROI sensitivity to investment options

Baseline scenario

Baseline conditions:

- $250,000 purchase

- 10% down payment

- 5% housing growth

- 25 year amortization

- $900/month rental cost

You are better off buying a house if you typically receive investment returns between 0-5% per annum, regardless of current interest rates.

As mentioned in the previous page, the inflection point for a 10% investment return is 6%. You are better off renting at interest rates above 6%, while there is a financial incentive to buy at interest rates below 6%.

If you consistently achieve returns in excess of 15% per annum, there is almost no financial incentive to buy a house in an average market like Toronto, especially with a fixed rate mortgage.

$600 monthly rent scenario

This graph shows the ROI sensitivity with $600/month rent.

ROI sensitivity to down payment

The down payment for a mortgage has a greater impact on the ROI when interest rates are low. At high interest rates the marginal impact between a 5% and 25% down payment is limited. This does not take into account mortgage insurance which is required for purchases with a down payment less than 20% in Canada.

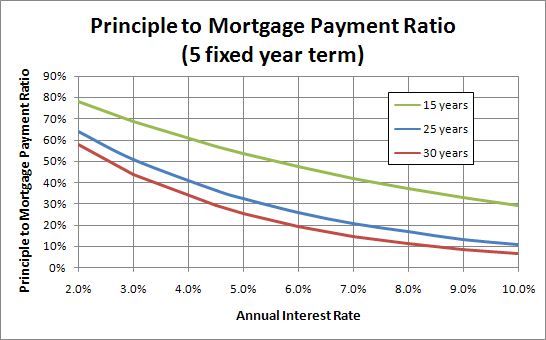

Principle to mortgage payment ratio

The division between your equity and the interest you pay the bank is based on several factors:

- amortization period

- interest rate (variable and fixed)

- term length

Currently you can get a variable interest rate mortgage at approximately 2%, and a fixed rate mortgage around 5%. At 2% you are effectively doubling your principle payment to your mortgage. The risk is that your mortgage payment will increase over time, while you principle contribution will diminish.

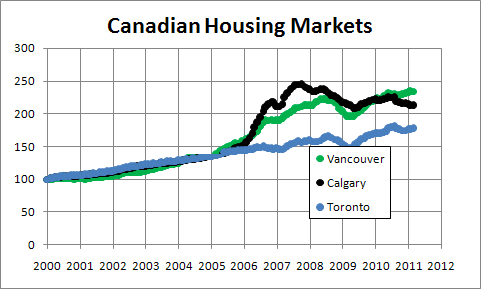

Canadian Housing Markets

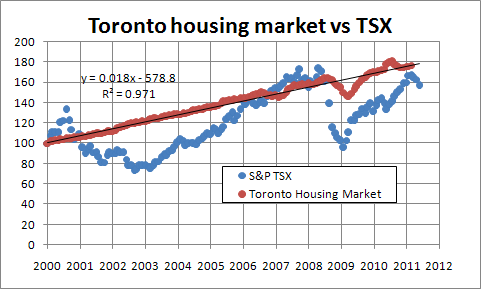

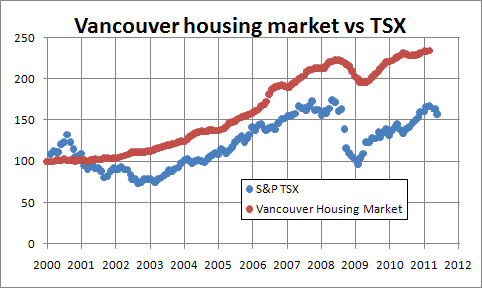

The charts below show the performance of Canadian housing markets relative to the stock market since 2000.

Toronto

The gap between Toronto real estate and the stock market is fairly minimal since 2000 at current prices. Toronto real estate has averaged a 5% yearly increase since 2000, with a significant dip during the past recession. The stock market has experienced more volatility, but periods of higher growth after the troughs.

Calgary

Prior to 2006 the housing market was comparable to Toronto. Calgary had a period of phenomenal growth between 2006 and 2008, thanks to world energy prices. The Calgary housing market has underperformed the stock market since 2009.

Vancouver

The Vancouver housing market has essentially outperformed the stock market since 2000.

Conclusion

I wrote this blog post to convince myself that buying a house doesn’t always make financial sense. I think Freud called that rationalization?

The reality is buying a home is likely the best investment option in most scenarios, but I don’t think I fit in that form. I would bet that Canadians generally have these attributes:

- invest their money in fairly conservative financial instruments

- live in urban areas with moderate growth in housing prices

- do not pursue graduate studies

- do not move to other provinces / countries

It doesn’t look like I have finished moving between provinces and I am still tempted by graduate studies. I can happily pay my rent each month without regret. At least for now.

If you are still interested in this topic, check out this article on the Financial Post.

Leave your response!